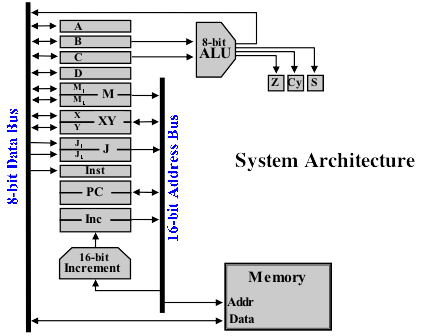

In this post I’ll continue to try and explain away the various bits of the architecture that will make up my relay computer project — this time it’s the memory. Here again is the architecture I’ll be building against (from the Harry Porter Relay Computer)

In my last post I wrote about the computer registers, each of which can store a binary value — they’re typically very fast although there’s a fixed number of them (in this computer there’s eight ‘general registers’ A, B, C, D, M1, M2, X and Y). Needless to say we wouldn’t be able to do anything too exciting if we’re limited to only 8 storage slots and that’s where the memory comes in — it’s not as fast (relatively) as the registers but it can hold many, many more values.

You can think of memory as a set of pigeon holes with a finite number of slots/holes that can each hold one value at a time. Each hole has a unique label on it so that we can refer back to it and find a value we placed earlier. The memory in this computer holds 8-bit values (also known as one byte … 1 byte = 8 bits) in each slot and there are 32,768 slots in total. This memory would be described as 32K because it can hold 32 kilobytes or 32 x 1024 bytes — note that there’s 1024 bytes to a kilobyte rather than 1000 as you might expect because everything is based on binary and the base-2 numbering system again. It’s worth noting that the values that are put in memory only stick around as long as there’s a power supply connected — as soon as the power is gone so are the values. You may have heard of memory being described as RAM (Random Access Memory) — this is so called because you can access the values in memory in a random fashion, that is, in any order.

The memory takes an input from the address bus and we provide the address of the location in memory we’d like to access here. Once we have an address we can then either set the value in memory from the data bus or read the current value from memory on to the data bus. So, if we set 0000000011001110 on the address bus then we’d be looking at the 206th slot in memory. As you can see dealing with addresses in binary can be a bit of a mouthful so when programming the computer we tend to use hexadecimal (base-16) notation which is more concise. For those not familiar with hexadecimal (or hex for short) it uses the numbers 0-9 followed by the letters a-f (so a=10 and f=15). This is quite handy because a single hex digit covers all the values possible in a 4-bit binary value (so for example, e in hex = 1110 in binary). Given this then we can describe the 16-bit address 0000000011001110 as 00CE (more commonly this would be written as 0x00CE with the leading ‘0x’ so it’s clear it’s a hexadecimal value).

You may have noticed, if you’ve got a pretty sharp eye for these things, that the address bus is 16-bit which means it can hold 2^16 = 65536 unique values (the maximum value being 65535 or 0xFFFF) however our memory is 32K meaning there are 32768 unique slots (the last slot being number 32767 or 0x7FFF or 0111111111111111 in binary). Why the mismatch? Well, we don’t have to assign all of the address values/spaces to the memory - we might want to attach other devices to the computer later on which would sit on those other addresses. A good example of this would be a monochrome monitor/screen. If you think of the monitor being divided up into rows and columns of pixels then each pixel would be either on or off (1 or 0). If you group up 8 pixels together then that’s one byte and each series of 8 pixels could be referred to with a unique address. If the monitor started at address 0x8000 then setting the value 10101010 at address 0x8002 would turn on a pattern of pixels starting at the 16th pixel of the first row. From a construction point of view dividing the address space into two halves makes things simpler for sending the address to the right location … taking the highest bit of the address then a zero means the address is destined for the memory whereas a one sends it to whatever I end up deciding to attach to the computer.

One thing very worthy of note for this computer is that it employs a Von Neumann architecture. In this type of architecture the program the computer is running is stored in the memory along with the data used by the actual program itself. This makes things simpler compared with a Harvard architecture where the data store is physically separate from the program storage (although the Harvard architecture does have other advantages such as you can read the next program instruction whilst moving data around due to the dedicated buses — as always with these things there’s a trade off). An interesting side effect of storing the computer program in the same memory as data is that the programmer can design a program that modifies itself while it is running which can make the program either very efficient or very hard to debug when things go wrong depending on your viewpoint ;)

So, there’s now just two parts of the architecture left to discuss: the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) and how a program actually executes and controls the computer.